At the end of 2019, an unknown pathogen was first isolated from three people with pneumonia-like symptoms in Wuhan, China. Scientists later identified it as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It only took 90 days for the highly contagious virus to conquer the whole world. Today, the virus had infected over 197 million people worldwide, and the number of deaths had totaled more than 4.1 million.

As we move into the second year of living with the disease, newer scientific discoveries to fight the virus bring hope. We are now optimistic about the development, equitable distribution, and access to safe COVID-19 vaccines to provide acquired immunity against the virus. Around the world, several different types of potential vaccines are in development. If you are still thinking of getting vaccinated, bookmark this article, open a new tab and register for the closest available vaccine slot. The potential benefits of vaccination far outweigh the potential risks. The internet is flooded with news reports of infection among unvaccinated people (here, here, and here). It is imperative on your part to do your bit to protect yourself and your community. According to the Central for Disease Control and Prevention (USA),

The best COVID-19 vaccine is the first one that is available to you. Do not wait for a specific brand.

Two of the widely implemented COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines are:

- The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (Approved for people 12 years of age and older)

- The Moderna vaccine (Approved for people 18 years of age and older)

But, even before we talk about the mRNA-based vaccines, what does the transcriptome of a SARS-CoV-2 patient look like? To answer this question, this article has been divided into the following sections:

- A short primer on RNA

- RNA therapies in general (with a focus on mRNA vaccines)

- The transcriptome

Let’s begin.

The curious case of the marvelous messenger — RNA

Ribonucleic Acid

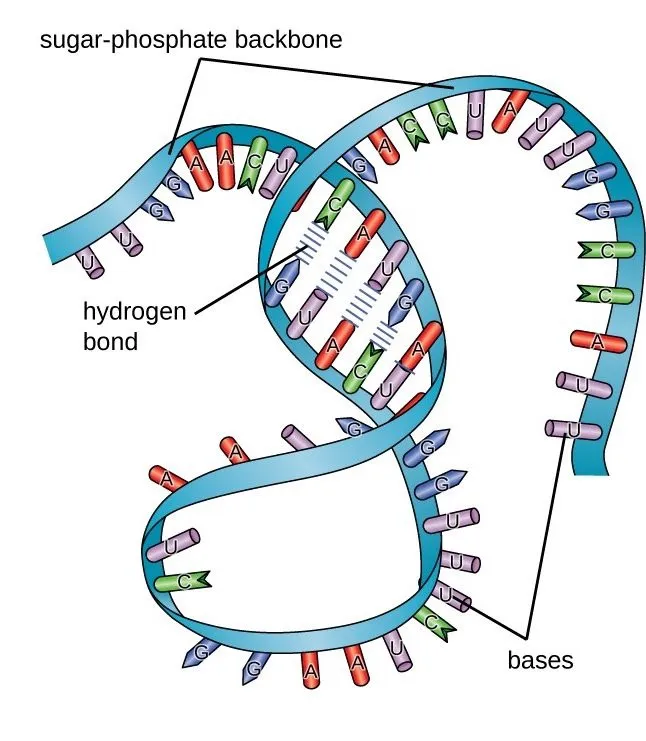

Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) is an important biological macromolecule that is present in our cells. RNA molecules carry essential genetic information and are rightfully dubbed as messengers. Chemically it differs from the DNA molecule in three basic aspects:

- RNA is a single-stranded molecule as opposed to double-stranded DNA.

- The sugar-phosphate “backbone” of the RNA molecule (shown in the picture above) is made up of ribose instead of deoxyribose.

- The complementary base to adenine in RNA is uracil instead of thymine.

Here’s a quick rundown on the different types of RNA molecules that is relevant to this article:

The translators:

- mRNA (messenger RNA): transfers information from the genes to the ribosome where proteins are made.

- rRNA (ribosomal RNA): forms the primary component of ribosomes and catalyzes the assembly of amino acids into protein chains.

- tRNA (transfer RNA): decodes the information present in the mRNA and helps add amino acids to a protein chain.

(I would encourage the reader to read up on the other types of RNA molecules not covered here: micro RNA, small nuclear RNA, small nucleolar RNA, and long intervening non-coding RNA)

RNA therapies — a candle in the dark

In the 2019 article titled “It’s time for scientists to shout about RNA therapies” published in Nature, Dr. Lorna Harries argued that,

One reason that RNA-based approaches are the lesser-known and seldom-seen sibling of DNA therapies might be the evident complexity of RNA biology, and the perceived difficulties in talking about it to a non-scientific audience.

The public perception of gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9 has been completely different from that of RNA therapies. Although attractive, manipulating DNA sequences to repair genetic alterations comes with its own set of challenges. They are unidirectional changes and can be inherited. RNA therapies, on the other hand, make temporary changes on the output of a gene (the protein) instead of changing the actual sequence [1].

So how do mRNA vaccines work? Are they safe? And how do they differ from traditional vaccines?

But first, let’s take a quick recap of how our body’s immune system works.

Our immune system

When a virus enters your body, it attaches itself to one of your healthy cells. The virus then starts injecting its genomic material (DNA/RNA) into the cell. As discussed in the section above, these are like blueprints containing information on what the cells have to make. In short, the RNA from the virus directs your cell to produce multiple copies of the same virus (thereby infecting even more cells), essentially turning it into a germ factory.

But this is not a rare occurrence or a brand new event. Evolution has taught our body’s immune system to turn itself on and fight against any intruder that doesn’t belong. The only catch? It takes a few days to recognize this intruder, tag them and destroy them. By that time, the virus has replicated many many times and you start feeling the symptoms of whatever has infected you.

Enter Vaccines

Vaccines provide protection against infections by training our immune system to recognize and fight off an intruder even before it has entered our body. It’s like a shoot-on-sight order issued by the body’s defense system to ward off any future reinfections.

How do mRNA vaccines work?

The following is the widely circulated image of the COVID-19 virus with its distinctive spikes. The spikes allow the virus to attach itself to a healthy cell, transfer the genetic information and direct the cell to produce many copies of the same.

The virus with its distinctive spikes

This is where mRNA vaccines come into the picture. Researchers have sequenced the virus’s RNA and isolated the part that is responsible for producing the spikes (also known as the spike protein). Armed with this information (the RNA sequence), the researchers created the mRNA (or messenger RNA) that gives instructions to the cell. In this case, the mRNA was coded with instructions to build the spike proteins of the coronavirus.

In simple terms, the mRNA vaccines contain instructions to create a portion (spikes) of the virus in large volumes.

The immune system takes some time to learn these instructions and then provides protection against any future infections. What’s interesting about mRNA vaccines is that it is relatively quick to develop once we know the RNA sequence of the virus. Currently, mRNA vaccines are used to treat a wide variety of diseases, including several forms of cancer, ebola, influenza, and so on [2].

That’s it. Let’s now slowly ease into the fascinating world of analyzing these mRNA sequences by studying the transcriptome.

Transcriptome

Based on the definition of Scitable,

A transcriptome is the full range of messenger RNA, or mRNA, molecules expressed by an organism. The term “transcriptome” can also be used to describe the array of (messenger RNA) transcripts produced in a particular cell or tissue type.

Note: A single gene can produce multiple different mRNAs (or transcripts). The transcript you observe at a particular point in time depends on the tissue, environmental factors, developmental stages, and so on. In fact, thousands of transcripts are produced every second in a given cell.

We will use an example from the ongoing pandemic to understand what it is. COVID-19 is a respiratory disease and it affects the lungs of the infected person. In some cases, it causes inflammation in the tiny air sacs located inside the lungs.

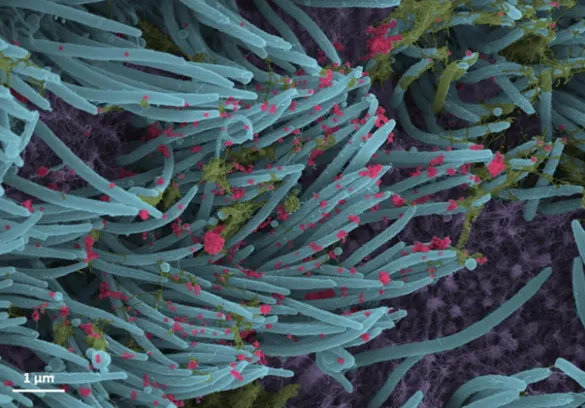

Colorized scanning electron microscope of COVID-19 affected lung cells

This colorized scanning electron microscope (SEM) image published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine [3], came out of the lab of Dr. Camille Ehre at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The lung cells (purple) were infected by the many thousands of coronavirus particles (red). The inner surface of the airways is covered by hair-like cilia (in blue) and helps to clear mucus (yellow-green).

Now the transcriptome will tell us which genes are turned on or off in the different lung cells shown above.

A beginner’s introduction to RNA-seq

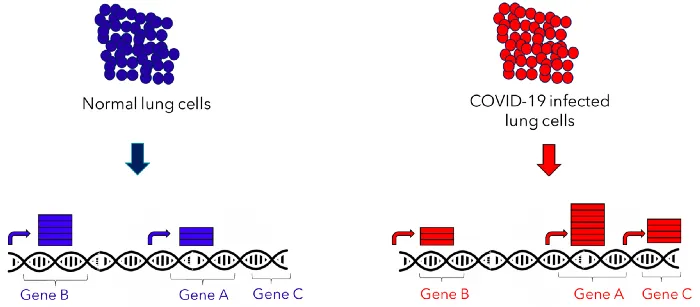

Let’s start with an example of a bunch of normal (in blue) and COVID-19 infected (abnormal) lung cells (in red). It is pretty obvious that the abnormal cells would behave differently and contribute towards disease severity.

What is the underlying genetic cause that is responsible for the infected lung cells to behave differently than the normal cells?

The straightforward way to determine this would be to look at the changes in gene expression. Cells are made up of chromosomes which in turn are made up of genes. Wikipedia states,

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect.

Normal lung cells: In the figure above, genes A and B are active (generate proteins) and gene C is inactive for the normal lung cells. Also, gene B is transcribed to a greater extent as compared to gene A (blue rectangles).

In general, the more a gene is transcribed, the more protein that will be made. — Khan Academy

COVID-19 infected lung cells: Here, all three genes are active (“on”), and gene A is transcribed more as compared to genes B and C.

Also, gene A belonging to the infected cells is transcribed to a greater extent than gene A belonging to the normal cells.

High-throughput next-generation sequencing technologies tell us which genes can generate proteins (are active) and by how much they are transcribed. Consequently, the function of a cell is dependent on the amount and types of mRNA molecules present.

Summary

- RNA ((messenger RNA) is an important biological macromolecule that carries the instructions to make proteins.

- RNA therapies (such as mRNA vaccines) are relatively new and is being used actively to fight the COVID-19 virus.

- These vaccines carry instructions to create a portion of the virus (spikes) in large volumes inside our cells.

- The transcriptome refers to the full range of mRNA transcripts produced by a cell or a tissue type.

- RNA-sequencing technologies tell us which genes are active and by how much they are transcribed.

Additional reading/watching materials:

- Khan Academy videos on Transcription and RNA processing.

- Statquest videos (scroll down to the section titled: High throughput sequencing analysis) on RNA-seq, DESeq2, FPKM, TPM, etc.

- WHO article on COVID-19 vaccines.

References:

- It’s time for scientists to shout about RNA therapies. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03074-6

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M., Porter, F. et al. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 261–279 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2017.243

- SARS-CoV-2 infection of airway cells. Ehre C. NEJM. 2020 Sep 3;383(10):969.

Image credits:

- https://microbenotes.com/rna-properties-structure-types-and-functions/

- https://www.cancercenter.com/community/blog/2020/04/covid-support-immune-system

- https://www.fredhutch.org/en/news/center-news/2020/04/covid19-virus-spike-structure.html

- https://www.med.unc.edu/marsicolunginstitute/directory/camille-ehre-phd/

Keywords

SARS-CoV-2, transcriptome, virus